|

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Inca Lands Content Page Click Here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

IV FLAMINGO LAKE THE Parinacochas Basin is at an

elevation of between

11,500 and 12,000 feet above sea level. It is about 150 miles northwest

of

Arequipa and 170 miles southwest of Cuzco, and enjoys a fair amount of

rainfall. The lake is fed by springs and small streams. In past

geological

times the lake, then very much larger, had an outlet not far from the

town of

Puyusca. At present Parinacochas has no visible outlet. It is possible

that the

large springs which we noticed as we came up the valley by Puyusca may

be fed from

the lake. On the other hand, we found numerous small springs on the

very

borders of the lake, generally occurring in swampy hillocks — built up

perhaps

by mineral deposits — three or four feet higher than the surrounding

plain.

There are very old beach marks well above the shore. The natives told

us that

in the wet season the lake was considerably higher than at present,

although we

could find no recent evidence to indicate that it had been much more

than a

foot above its present level. Nevertheless a rise of a foot would

enlarge the

area of the lake considerably. When making preparations in New

Haven for the

“bathymetric survey of Lake Parinacochas,” suggested by Sir Clements

Markham,

we found it impossible to discover any indication in geographical

literature as

to whether the depth of the lake might be ten feet or ten thousand

feet. We

decided to take a chance on its not being more than ten hundred feet.

With the

kind assistance of Mr. George Bassett, I secured a thousand feet of

stout fish

line, known to anglers as “24 thread,” wound on a large wooden reel for

convenience in handling. While we were at Chuquibamba Mr. Watkins had

spent

many weary hours inserting one hundred and sixty-six white and red

cloth

markers at six-foot intervals in the strands of this heavy line, so

that we

might be able more rapidly to determine the result in fathoms. Arrived at a low peninsula on

the north shore of the

lake, Tucker and I pitched our camp, sent our mules back to Puyusca for

fodder,

and set up the Acme folding boat, which we had brought so many miles on

mule-back, for the sounding operations. The “Acme” proved easy to

assemble,

although this was our first experience with it. Its lightness enabled

it to be

floated at the edge of the lake even in very shallow water, and its

rigidity

was much appreciated in the late afternoon when the high winds raised a

vicious

little “sea.” Rowing out on waters which we were told by the natives

had never

before been navigated by craft of any kind, I began to take soundings.

Lake Titicaca

is over nine hundred feet deep. It would be aggravating if Lake

Parinacochas

should prove to be over a thousand, for I had brought no extra line.

Even nine

hundred feet would make sounding slow work, and the lake covered an

area of

over seventy square miles. It was with mixed feelings of

trepidation and

expectation that I rowed out five miles from shore and made a sounding.

Holding

the large reel firmly in both hands, I cast the lead overboard. The

reel gave a

turn or two and stopped. Something was wrong. The line did not run out.

Was the

reel stuck? No, the apparatus was in perfect running order. Then what

was the

matter? The bottom was too near! Alas for all the pains that Mr.

Bassett had

taken to put a thousand feet of the best strong 24-thread line on one

reel!

Alas for Mr. Watkins and his patient insertion of one hundred and

sixty-six

“fathom-markers”! The bottom of the lake was only four feet away from

the

bottom of my boat! After three or four days of strenuous rowing up and

down the

eighteen miles of the lake’s length, and back and forth across the

seventeen

miles of its width, I never succeeded in wetting Watkins’s first

marker!

Several hundred soundings failed to show more than five feet of water

anywhere.

Possibly if we had come in the rainy season we might at least have wet

one

marker, but at the time of our visit (November, 1911), the lake had a

maximum

depth of 4 1/2 feet. The satisfaction of making this slight

contribution to

geographic knowledge was, I fear, lost in the chagrin of not finding a

really

noteworthy body of water. Who would have thought that so

long a lake could be

so shallow? However, my feelings were soothed by remembering the story

of the

captain of a man-of-war who was once told that the salt lake near one

of the

red hills between Honolulu and Pearl Harbor was reported by the natives

to be

“bottomless.” He ordered one of the ship’s

heavy boats to be

carried from the shore several miles inland to the salt lake, at great

expenditure of strength and labor. The story told me in my boyhood does

not say

how much sounding line was brought. Anyhow, they found this

“fathomless” body

of water to be not more than fifteen feet deep.

Notwithstanding my disappointment at the depth of Parinacochas, I was

very glad that we had brought the little folding boat, for it enabled

me to

float gently about among the myriads of birds which use the shallow

waters of

the lake as a favorite feeding ground; pink flamingoes, white gulls,

small

“divers,” large black ducks, sandpipers, black ibis, teal ducks, and

large

geese. On the hulks were ground owls and woodpeckers. It is not

surprising that

the natives should have named this body of water “Parinacochas” (Parina

=

“flamingo,” cochas = “lake”). The flamingoes are

here in incredible

multitudes; they far outnumber all other birds, and as I have said,

actually

make the shallow waters of the lake look pink. Fortunately they had not

been

hunted for their plumage and were not timid. After two days of

familiarity with

the boat they were willing to let me approach within twenty yards

before

finally taking wing. The coloring, in this land of drab grays and

browns, was a

delight to the eye. The head is white, the beak black, the neck white

shading

into salmon-pink; the body pinkish white on the back, the breast white,

and the

tail salmon-pink. The wings are salmon-pink in front, but the tips and

the

under-parts are black. As they stand or wade in the water their general

appearance is chiefly pink-and-white. When they rise from the water,

however,

the black under-parts of the wings became strikingly conspicuous and

cause a

flock of flying flamingoes to be a wonderful contrast in

black-and-white. When

flying, the flamingo seems to keep his head moving steadily forward at

an even

pace, although the ropelike neck undulates with the slow beating of the

wings.

I could not be sure that it was not an optical delusion. Nevertheless,

I

thought the heavy body was propelled irregularly, while the head moved

forward

at uniform speed, the difference being caught up in the undulations of

the

neck.

The flamingo is an amusing bird

to watch. With its

haughty Roman nose and long, ropelike neck, which it coils and twists

in a most

incredible manner, it seems specially intended to distract one’s mind

from

bathymetric disappointments. Its hoarse croaking, “What

is it,” “What is

it,” seemed

to express deep-throated sympathy with the sounding operations. On one

bright

moonlight night the flamingoes were very noisy, keeping up a continual

clatter

of very hoarse “What-is-it’s.” Apparently they failed to find out the

answer in

time to go to bed at the proper time, for next morning we found them

all sound

asleep, standing in quiet bays with their heads tucked under their

wings.

During the course of the forenoon, when the water was quiet, they waded

far out

into the lake. In the afternoon, as winds and waves arose, they came in

nearer

the shores, but seldom left the water. The great extent of shallow

water in

Parinacochas offers them a splendid, wide feeding ground. We wondered

where

they all came from. Apparently they do not breed here. Although there

were

thousands and thousands of birds, we could find no flamingo nests,

either old

or new, search as we would. It offers a most interesting problem for

some

enterprising biological explorer. Probably Mr. Frank Chapman will some

day

solve it. Next in number to the

flamingoes were the beautiful

white gulls (or terns?), looking strangely out of place in this Andean

lake

11,500 feet above the sea. They usually kept together in flocks of

several

hundred. There were quantities of small black divers in the deeper

parts of the

lake where the flamingoes did not go. The divers were very quick and

keen, true

individualists operating alone and showing astonishing ability in

swimming long

distances under water. The large black ducks were much more fearless

than the

flamingoes and were willing to swim very near the canoe. When

frightened, they

raced over the water at a tremendous pace, using both wings and feet in

their

efforts to escape. These ducks kept in large flocks and were about as

common as

the small divers. Here and there in the lake were a few tiny little

islands,

each containing a single deserted nest, possibly belonging to an ibis

or a

duck. In the banks of a low stream near our first camp were holes made

by woodpeckers,

who in this country look in vain for trees and telegraph poles. Occasionally, a mile or so from

shore, my boat would

startle a great amphibious ox standing in the water up to his middle,

calmly

eating the succulent water grass. To secure it he had to plunge his

head and

neck well under the surface. While I was raising blisters

and frightening oxen

and flamingoes, Mr. Tucker triangulated the Parinacochas Basin, making

the

first accurate map of this vicinity. As he carried his theodolite from

point to

point he often stirred up little ground owls, who gazed at him with

solemn,

reproachful looks. And they were not the only individuals to regard his

activities with suspicion and dislike. Part of my work was to construct

signal

stations by piling rocks at conspicuous points on the well-rounded

hills so as

to enable the triangulation to proceed as rapidly as possible. During

the night

some of these signal stations would disappear, torn down by the

superstitious

shepherds who lived in scattered clusters of huts and declined to have

strange

gods set up in their vicinity. Perhaps they thought their pastures were

being

preempted. We saw hundreds of their sheep and cattle feeding on flat

lands

formerly the bed of the lake. The hills of the Parinacochas Basin are

bare of

trees, and offer some pasturage. In some places they are covered with

broken

rock. The grass was kept closely cropped by the degenerate descendants

of sheep

brought into the country during Spanish colonial days. They were small

in size

and mostly white in color, although there were many black ones. We were

told

that the sheep were worth about fifty cents apiece here. On our first arrival at

Parinacochas we were left

severely alone by the shepherds; but two days later curiosity slowly

overcame

their shyness, and a group of young shepherds and shepherdesses

gradually

brought their grazing flocks nearer and nearer the camp, in order to

gaze

stealthily on these strange visitors, who lived in a cloth house,

actually

moved over the forbidding waters of the lake, and busied themselves

from day to

day with strange magic, raising and lowering a glittering glass eye on

a

tripod. The women wore dresses of heavy material, the skirts reaching

halfway

from knee to ankle. In lieu of hats they had small variegated shawls,

made on

hand looms, folded so as to make a pointed bonnet over the head and

protect the

neck arid shoulders from sun and wind. Each woman was busily spinning

with a

hand spindle, but carried her baby and its gear and blankets in a

hammock or sling

attached to a tump-line that went over her head. These sling carry-alls

were

neatly woven of soft wool and decorated with attractive patterns. Both

women

and boys were barefooted. The boys wore old felt hats of native

manufacture,

and coats and long trousers much too large for them. At one end of the upland basin

rises the graceful

cone of Mt. Sarasara. The view of its snow-capped peak reflected in the

glassy

waters of the lake in the early morning was one long to be remembered.

Sarasara

must once have been much higher than it is at present. Its volcanic

cone has

been sharply eroded by snow and ice. In the days of its greater

altitude, and

consequently wider snow fields, the melting snows probably served to

make

Parinacochas a very much larger body of water. Although we were here at

the

beginning of summer, the wind that came down from the mountain at night

was

very cold. Our minimum thermometer registered 22° F. near the banks of

the lake

at night. Nevertheless, there was only a very thin film of ice on the

borders

of the lake in the morning, and except in the most shallow bays there

was no

ice visible far from the bank. The temperature of the water at 10:00 A.M. near the shore, and

ten inches below

the surface, was 61° F., while farther out it was three or four degrees

warmer.

By noon the temperature of the water half a mile from shore was 67.5°

F.

Shortly after noon a strong wind came up from the coast, stirring up

the

shallow water and cooling it. Soon afterwards the temperature of the

water

began to fall, and, although the hot sun was shining brightly almost

directly

overhead, it went down to 65° by 2:30 P.M. The water of the lake is

brackish, yet we were able

to make our camps on the banks of small streams of sweet water,

although in

each case near the shore of the lake. A specimen of the water, taken

near the

shore, was brought back to New Haven and analyzed by Dr. George S.

Jamieson of

the Sheffield Scientific School. He found that it contained small

quantities of

silica, iron phosphate, magnesium carbonate, calcium carbonate, calcium

sulphate, potassium nitrate, potassium sulphate, sodium borate, sodium

sulphate, and a considerable quantity of sodium chloride. Parinacochas

water

contains more carbonate and potassium than that of the Atlantic Ocean

or the

Great Salt Lake. As compared with the salinity of typical “salt”

waters, that

of Lake Parinacochas occupies an intermediate position, containing more

than

Lake Koko-Nor, less than that of the Atlantic, and only one twentieth

the

salinity of the Great Salt Lake. When we moved to our second

camp the Tejada brothers

preferred to let their mules rest in the Puyusca Valley, where there

was

excellent alfalfa forage. The arrieros engaged at

their own expense a

pack train which consisted chiefly of Parinacochas burros. It is the

custom

hereabouts to enclose the packs in large-meshed nets made of rawhide

which are

then fastened to the pack animal by a surcingle. The Indians who came

with the

burro train were pleasant-faced, sturdy fellows, dressed in “store

clothes” and

straw hats. Their burros were as cantankerous as donkeys can be, never

fractious or flighty, but stubbornly resisting, step by step, every

effort to

haul them near the loads. Our second camp was near the

village of Incahuasi,

“the house of the Inca,” at the northwestern corner of the basin.

Raimondi

visited it in 1863. The representative of the owner of Parinacochas

occupies

one of the houses. The other buildings are used only during the third

week in

August, at the time of the annual fair. In the now deserted plaza were

many low

stone rectangles partly covered with adobe and ready to be converted

into

booths. The plaza was surrounded by long, thatched buildings of adobe

and

stone, mostly of rough ashlars. A few ashlars showed signs of having

been carefully

dressed by ancient stonemasons. Some loose ashlars weighed half a ton

and had

baffled the attempts of modern builders. In constructing the large

church, advantage was

taken of a beautifully laid wall of close-fitting ashlars. Incahuasi

was well

named; there had been at one time an Inca house here, possibly a temple

— lakes

were once objects of worship — or rest-house, constructed in order to

enable

the chiefs and tax-gatherers to travel comfortably over the vast

domains of the

Incas. We found the slopes of the hills of the Parinacochas Basin to be

well

covered with remains of ancient terraces. Probably potatoes and other

root

crops were once raised here in fairly large quantities. Perhaps

deforestation

and subsequent increased aridity might account for the desertion of

these

once-cultivated lands. The hills west of the lake are intersected by a

few dry

gulches in which are caves that have been used as burial places. The

caves had

at one time been walled in with rocks laid in adobe, but these walls

had been

partly broken down so as to permit the sepulchers to be rifled of

whatever

objects of value they might have contained. We found nine or ten skulls

lying

loose in the rubble of the caves. One of the skulls seemed to have been

trepanned. On top of the ridge are the

remains of an ancient

road, fifty feet wide, a broad grassy way through fields of loose

stones. No

effort had been made at grading or paving this road, and there was no

evidence

of its having been used in recent times. It runs from the lake across

the ridge

in a westerly direction toward a broad valley, where there are many

terraces

and cultivated fields; it is not far from Nasca. Probably the stones

were

picked up and piled on each side to save time in driving caravans of

llamas

across the stony ridges. The llama dislikes to step over any obstacle,

even a

very low wall. The grassy roadway would certainly encourage the

supercilious

beasts to proceed in the desired direction. In many places on the hills

were to be seen outlines

of large and small rock circles and shelters erected by herdsmen for

temporary

protection against the sudden storms of snow and hail which come up with

unexpected fierceness at this elevation (12,000 feet). The shelters

were in a

very ruinous state. They were made of rough, scoriaceous lava rocks.

The

circular enclosures varied from 8 to 25 feet in diameter. Most of them

showed

no evidences whatever of recent occupation. The smaller walls may have

been the

foundation of small circular huts. The larger walls were probably

intended as

corrals, to keep alpacas and llamas from straying at night and to guard

against

wolves or coyotes. I confess to being quite mystified as to the age of

these

remains. It is possible that they represent a settlement of shepherds

within

historic times, although, from the shape and size of the walls, I am

inclined

to doubt this. The shelters may have been built by the herdsmen of the

Incas.

Anyhow, those on the hills west of Parinacochas had not been used for a

long

time. Nasca, which is not very far away to the northwest, was the

center of one

of the most artistic pre-Inca cultures in Peru. It is famous for its

very

delicate pottery. Our third camp was

on the south side of the lake. Near us the traces of the ancient road

led to

the ruins of two large, circular corrals, substantiating my belief that

this

curious roadway was intended to keep the llamas from straying at will

over the

pasture lands. On the south shores of the lake there were more signs of

occupation than on the north, although there is nothing so clearly

belonging to

the time of the Incas as the ashlars and finely built wall at

Incahuasi. On top

of one of the rocky promontories we found the rough stone foundations

of the

walls of a little village. The slopes of the promontory were nearly

precipitous

on three sides. Forty or fifty very primitive dwellings had been at one

time

huddled together here in a position which could easily be defended. We

found

among the ruins a few crude potsherds and some bits of obsidian. There

was

nothing about the ruins of the little hill village to give any

indication of

Inca origin. Probably it goes back to pre-Inca days. No one could tell

us

anything about it. If there were traditions concerning it they were

well

concealed by the silent, superstitious shepherds of the vicinity.

Possibly it

was regarded as an unlucky spot, cursed by the gods. The neighboring slopes showed

faint evidences of

having been roughly terraced and cultivated. The tutu potato would grow

here, a

hardy variety not edible in the fresh state, but considered highly

desirable

for making potato flour after having been repeatedly frozen and its

bitter

juices all extracted. So would other highland root crops of the

Peruvians, such

as the oca, a relative of our sheep sorrel, the aņu,

a kind of nasturtium,

and the ullucu (ullucus tuberosus). On the flats near the shore

were large corrals still

kept in good repair. New walls were being built by the Indians at the

time of

our visit. Near the southeast corner of the lake were a few modern huts

built

of stone and adobe, with thatched roofs, inhabited by drovers and

shepherds. We

saw more cattle at the east end of the lake than elsewhere, but they

seemed to

prefer the sweet water grasses of the lake to the tough bunch-grass on

the

slopes of Sarasara. Viscachas

were common amongst the gray lichen-covered rocks. They are hunted for

their

beautiful pearly gray fur, the “chinchilla” of commerce; they are also

very

good eating, so they have disappeared from the more accessible parts of

Peru.

One rarely sees them, although they may be found on bleak uplands in

the

mountains of Uilcapampa, a region rarely visited by any one on account

of

treacherous bogs and deep tarns. Writers sometimes call viscachas

“rabbit-squirrels.” They have large, rounded ears, long hind legs, a

long,

bushy tail, and do look like a cross between a rabbit and a gray

squirrel. Surmounting one of the higher

ridges one day, I came

suddenly upon an unusually large herd of wild vicuņas. It included more

than

one hundred individuals. Their relative fearlessness also testified to

the

remoteness of Parinacochas and the small amount of hunting that is done

here.

Vicuņas have never been domesticated, but are often hunted for their

skins.

Their silky fleece is even finer than alpaca. The more fleecy portions

of their

skins are sewed together to make quilts, as soft as eider down and of a

golden

brown color. After Mr. Tucker finished his

triangulation of the

lake I told the arrieros to find the shortest road

home. They smiled,

murmured “Arequipa,” and started south. We soon came to the rim of the

Maraicasa Valley where, peeping up over one of the hills far to the

south, we

got a little glimpse of Coropuna. The Maraicasa Valley is well

inhabited and

there were many grain fields in sight, although few seemed to be

terraced. The

surrounding hills were smooth and well rounded and the valley bottom

contained

much alluvial land. We passed through it and, after dark, reached

Sondor, a

tiny hamlet inhabited by extremely suspicious and inhospitable drovers.

In the

darkness Don Pablo pleaded with the owners of a well-thatched hut, and

told

them how “important” we were. They were unwilling to give us any

shelter, so we

were forced to pitch our tent in the very rocky and dirty corral

immediately in

front of one of the huts, where pigs, dogs, and cattle annoyed us all

night. If

we had arrived before dark we might have received a different welcome.

As a

matter of fact, the herdsmen only showed the customary hostility of

mountaineers and wilderness folk to those who do not arrive in the

daytime,

when they can be plainly seen and fully discussed. The next morning we passed some

fairly recent lava

flows and noted also many curious rock forms caused by wind and sand

erosion.

We had now left the belt of grazing lands and once more come into the

desert.

At length we reached the rim of the mile-deep Caraveli Canyon and our

eyes were

gladdened at sight of the rich green oasis, a striking contrast to the

barren

walls of the canyon. As we descended the long, winding road we passed

many fine

specimens of tree cactus. At the foot of the steep descent we found

ourselves

separated from the nearest settlement by a very wide river, which it

was

necessary to ford. Neither of the Tejadas had ever been here before and

its

depths and dangers were unknown. Fortunately Pablo found a forlorn

individual

living in a tiny hut on the bank, who indicated which way lay safety.

After an

exciting two hours we finally got across to the desired shore. Animals

and men

were glad enough to leave the high, arid desert and enter the oasis of

Caraveli

with its luscious, green fields of alfalfa, its shady fig trees and

tall

eucalyptus. The air, pungent with the smell of rich vegetation, seemed

cooler

and more invigorating. We found at Caraveli a modern

British enterprise,

the gold mine of “La Victoria.” Mr. Prain, the Manager, and his

associates at

the camp gave us a cordial welcome, and a wonderful dinner which I

shall long

remember. After two months in the coastal desert it seemed like home.

During

the evening we learned of the difficulties Mr. Prain had had in

bringing his

machinery across the plateau from the nearest port. Our own troubles

seemed as

nothing. The cost of transporting on mule-back each of the larger

pieces of the

quartz stamping-mill was equivalent to the price of a first-class pack

mule. As

a matter of fact, although it is only a two days’ journey, pack

animals’ backs

are not built to survive the strain of carrying pieces of machinery

weighing five hundred pounds over

a desert

plateau up to an altitude of 4000 feet. Mules brought the machinery

from the

coast to the brink of the canyon, but no mule could possibly have

carried it

down the steep trail into Caraveli. Accordingly, a windlass had been

constructed on the edge of the precipice and the machinery had been

lowered,

piece by piece, by block and tackle. Such was one of the obstacles with

which

these undaunted engineers had had to contend. Had the man who designed

the

machinery ever traveled with a pack train, climbing up and down over

these

rocky stairways called mountain trails, I am sure that he would have

made his

castings much smaller.

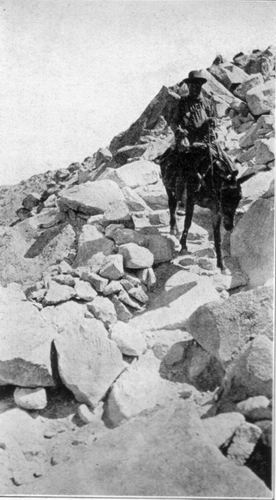

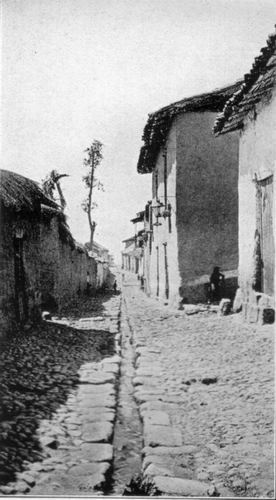

MR. TUCKER ON A MOUNTAIN TRAIL THE MAIN STREET OF NEAR CARAVELI CHUQUIBAMBA It is astonishing how often

people who ship goods to

the interior of South America fail to realize that no single piece

should be

any heavier than a pack animal can carry comfortably on one

side. One hundred and fifty pounds ought to be the extreme

limit of a unit. Even a large, strong mule will last only a few days on

such

trails as are shown in the accompanying illustration if the total

weight of his

cargo is over three hundred pounds. When a single piece weighs more

than two

hundred pounds it has to be balanced on the back of the animal. Then

the load

rocks, and chafes the unfortunate mule, besides causing great

inconvenience and

constant worry to the muleteers. As a matter of expediency it is better

to have

the individual units weigh about seventy-five pounds. Such a weight is

easier

for the arrieros to handle in the loading,

unloading, and reloading that

goes on all day long, particularly if the trail is up-and-down, as

usually

happens in the Andes. Furthermore, one seventy-five-pound unit makes a

fair

load for a man or a llama, two are right for a burro, and three for an

average

mule. Four can be loaded, if necessary, on a stout mule. The hospitable mining engineers

urged us to prolong

our stay at “La Victoria,” but we had to hasten on. Leaving the

pleasant shade

trees of Caraveli, we climbed the barren, desolate hills of coarse

gravel and

lava rock and left the canyon. We were surprised to find near the top

of the rise

the scattered foundations of fifty little circular or oval huts

averaging eight

feet in diameter. There was no water near here. Hardly a green thing of

any

sort was to be seen in the vicinity, yet here had once been a village.

It

seemed to belong to the same period as that found on the southern

slopes of the

Parinacochas Basin. The road was one of the worst we encountered

anywhere,

being at times merely a rough, rocky trail over and among huge piles of

lava

blocks. Several of the larger boulders were covered with pictographs.

They

represented a serpent and a sun, besides men and animals. Shortly afterwards we descended

to the Rio Grande

Valley at Callanga, where we pitched our camps among the most extensive

ruins

that I have seen in the coastal desert. They covered an area of one

hundred

acres, the houses being crowded closely together. It gave one a strange

sensation to find such a very large metropolis in what is now a

desolate

region. The general appearance of Callanga was strikingly reminiscent

of some

of the large groups of ruins in our own Southwest. Nothing about it

indicated

Inca origin. There were no terraces in the vicinity. It is difficult to

imagine

what such a large population could have done here, or how they lived.

The walls

were of compact cobblestones, rough-laid and stuccoed with adobe and

sand. Most

of the stucco had come off. Some of the houses had seats, or small

sleeping-platforms, built up at one end. Others contained two or three

small

cells, possibly storerooms, with neither doors nor windows. We found a

number

of burial cists — some square, others rounded — lined with small

cobblestones.

In one house, at the foot of “cellar stairs” we found a subterranean

room, or

tomb. The entrance to it was covered with a single stone lintel. In

examining

this tomb Mr. Tucker had a narrow escape from being bitten by a boba, a venomous snake, nearly three

feet in length, with vicious mouth, long fangs like a rattlesnake, and

a

strikingly mottled skin. At one place there was a low pyramid less than

ten

feet in height. To its top led a flight of rude stone steps. Among the ruins we found a

number of broken stone

dishes, rudely carved out of soft, highly porous, scoriaceous lava. The

dishes

must have been hard to keep clean! We also found a small stone mortar,

probably

used for grinding paint; a broken stone war club; and a broken compact

stone

mortar and pestle possibly used for grinding corn. Two stones, a foot

and a

half long, roughly rounded, with a shallow groove across the middle of

the

flatter sides, resembled sinkers used by fishermen to hold down large

nets,

although ten times larger than any I had ever seen used. Perhaps they

were to

tie down roofs in a gale. There were a few potsherds lying on the

surface of

the ground, so weathered as to have lost whatever decoration they once

had. We

did no excavating. Callanga offers an interesting field for

archeological

investigation. Unfortunately, we had heard nothing of it previously,

carne upon

it unexpectedly, and had but little time to give it. After the first

night camp

in the midst of the dead city we made the discovery that although it

seemed to

be entirely deserted, it was, as a matter of fact, well populated! I

was

reminded of Professor T. D. Seymour’s story of his studies in the ruins

of

ancient Greece. We wondered what the fleas live on ordinarily. Our next stopping-place was the

small town of

Andaray, whose thatched houses are built chiefly of stone plastered

with mud.

Near it we encountered two men with a mule, which they said they were

taking into

town to sell and were willing to dispose of cheaply. The Tejadas could

not

resist the temptation to buy a good animal at a bargain, although the

circumstances were suspicious. Drawing on us for six gold sovereigns,

they

smilingly added the new mule to the pack train; only to discover on

reaching

Chuquibamba that they had purchased it from thieves. We were able to

clear our arrieros of any

complicity in the theft.

Nevertheless, the owner of the stolen mule was unwilling to pay

anything for

its return. So they lost their bargain and their gold. We spent one

night in

Chuquibamba, with our friend Seņor Benavides, the sub-prefect, and once

more

took up the well-traveled route to Arequipa. We left the Majes Valley

in the

afternoon and, as before, spent the night crossing the desert. About three o’clock in the

morning — after we had

been jogging steadily along for about twelve hours in the dark and

quiet of the

night, the only sound the shuffle of the mules’ feet in the sand, the

only

sight an occasional crescent-shaped dune, dimly visible in the

starlight — the

eastern horizon began to be faintly illumined. The moon had long since

set.

Could this be the approach of dawn? Sunrise was not due for at least

two hours.

In the tropics there is little twilight preceding the day; “the dawn

comes up

like thunder.” Surely the moon could not be going to rise again! What

could be

the meaning of the rapidly brightening eastern sky? While we watched

and

marveled, the pure white light grew brighter and brighter, until we

cried out

in ecstasy as a dazzling luminary rose majestically above the horizon.

A

splendor, neither of the sun nor of the moon, shone upon us. It was the

morning

star. For sheer beauty, “divine, enchanting ravishment,” Venus that day

surpassed anything I have ever seen. In the words of the great Eastern

poet,

who had often seen such a sight in the deserts of Asia, “the morning

stars sang

together and all the sons of God shouted for joy.” |